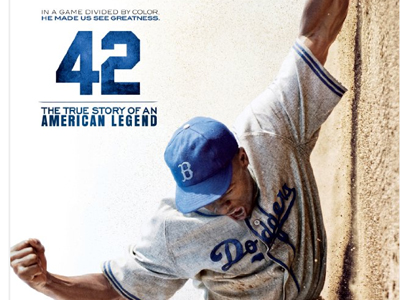

Welcome to the second entry of this year’s “Black History Month Film Reviews.” “God built me to last,” Jackie Robinson says at one point in the 2013 biographical film “42,” and, thankfully, his remarkable story is built the same way. Kenneth Turan stated in his review, “It would have to be to survive the full-dress Hollywood biopic treatment it gets in this film, which is unabashedly subtitled "The True Story of an American Legend."” Survive it does.

Welcome to the second entry of this year’s “Black History Month Film Reviews.” “God built me to last,” Jackie Robinson says at one point in the 2013 biographical film “42,” and, thankfully, his remarkable story is built the same way. Kenneth Turan stated in his review, “It would have to be to survive the full-dress Hollywood biopic treatment it gets in this film, which is unabashedly subtitled "The True Story of an American Legend."” Survive it does.

Turan goes on his review by saying, “You almost can't blame writer-director Brian Helgeland for taking an old-fashioned, earnest-to-a-fault approach to the genuinely heroic narrative of the Brooklyn Dodger who in 1947 — in a move masterminded by team General Manager Branch Rickey -- broke the Major League Baseball color barrier, led the Dodgers to the National League pennant and won rookie of the year honors.”

Turan continues by saying, “Robinson's story had so much drama in real life, and his sacrifice and pain made such a lasting influence, that "42" ends up being effective in its gee-whiz way almost in spite of itself. The film is so on-the-nose, it practically could have been made in 1947 (or 1950, when "The Jackie Robinson Story" starring the man himself hit theaters). But this is one square movie that you’ll have to let be that way.”

In casting the roles of Robinson and his wife, Rachael (who lived through all of this with him), Helgeland has made sharp choices, making actors good enough to give their characters more texture than the film is set up to allow. Robinson is played by Chadwick Boseman, who debuted playing another athlete, Syracuse University’s running back Floyd Little, in 2008’s “The Express.” Boseman brings real force and dignity to this role, as well as an intensity that will not be pushed around.

Turan noted in his review, “Taking on the helpmate role played by Ruby Dee in the 1950 film is the gifted Nicole Beharie, memorable in very different roles in "American Violet" and "Shame," who uses all of her skill to ensure that this is Rachel's story as well as Jackie's.”

It also helps that Helgeland does not softly show the savage, hideous nature of the racism that Robinson had to deal with. What’s really effective in this movie is a part showing the nonstop rage felt by Robinson by the Philadelphia Phillies Manager Ben Chapman, played by Alan Tudyk – abuse Robinson had promised not to respond to.

For viewers of today watching this, especially children, who may not have heard this type of language in real life, prejudice as naked as this is tough to experience, even on a movie screen.

Turan stated, “More often than we'd like, however, "42" gives us standard tropes like unhappy stories getting told on stormy nights and women getting inexplicably sick and not realizing it's because they're pregnant.” Racial barriers may disappear, but some things seriously never change.

Before we go into Robinson’s neighborhood, we meet Rickey, gamely played by Harrison Ford in padded three-piece suits and bow ties, in spring 1945. Bad-tempered and argumentative, the general manager is determined to “bring a Negro ballplayer to the Brooklyn Dodgers,” even though amazed associates warn him that “if we break an unwritten law, you’ll be an outcast.” Rickey replies like a visionary more than an executive: “I don’t know who he is, but he’s coming.”

The audience, obviously, knows exactly who “he” is, and soon we catch up with Robinson, playing for the Negro League’s Kansas City Monarchs. In a scene showcasing Robinson’s wisdom as well as fire, he maneuvers a Southern gas station owner into allowing the black ballplayers to use a whites-only restroom.

Next comes the classic meeting with Rickey, who race-baits Robinson in order to give him a taste of what is to come. The general manager lets Robinson know that he must control his temper – no matter what is said at him – if this risk is to succeed.

When Robinson thinks testily if Rickey is looking for someone without any guts, Rickey memorable replies, “I want a player who’s got the guts not to fight back.” And so the film’s dramatic tension gets established: Will Robinson be able to restrain himself, and how will he do it?

With African American sportswriter Wendell Smith, played by Andre Holland, as advisor, Robinson deals with racism not only from opponents but also referees, journalists and even members of his own team, who petition Rickey not to let him play. He has difficulty adjusting to being in public eye off the field but displays a ferocious competitiveness on the diamond that causes Dodgers Manager Leo Durocher, played by Christopher Meloni, to comment, “He didn’t come to play, he came to kill.”

Robinson’s combination of strength, restraint and passion for the game was stunning. You can’t help getting caught up in this story, even as you are wishing the narrative was sharper than it is.

If you get the chance to watch this movie, do so, you will absolutely love it. Especially since it’s about the very first African American ballplayer in the Major League during segregation, which is really powerful.

Look out tomorrow for my third entry on a Valentine’s Day movie.

No comments:

Post a Comment